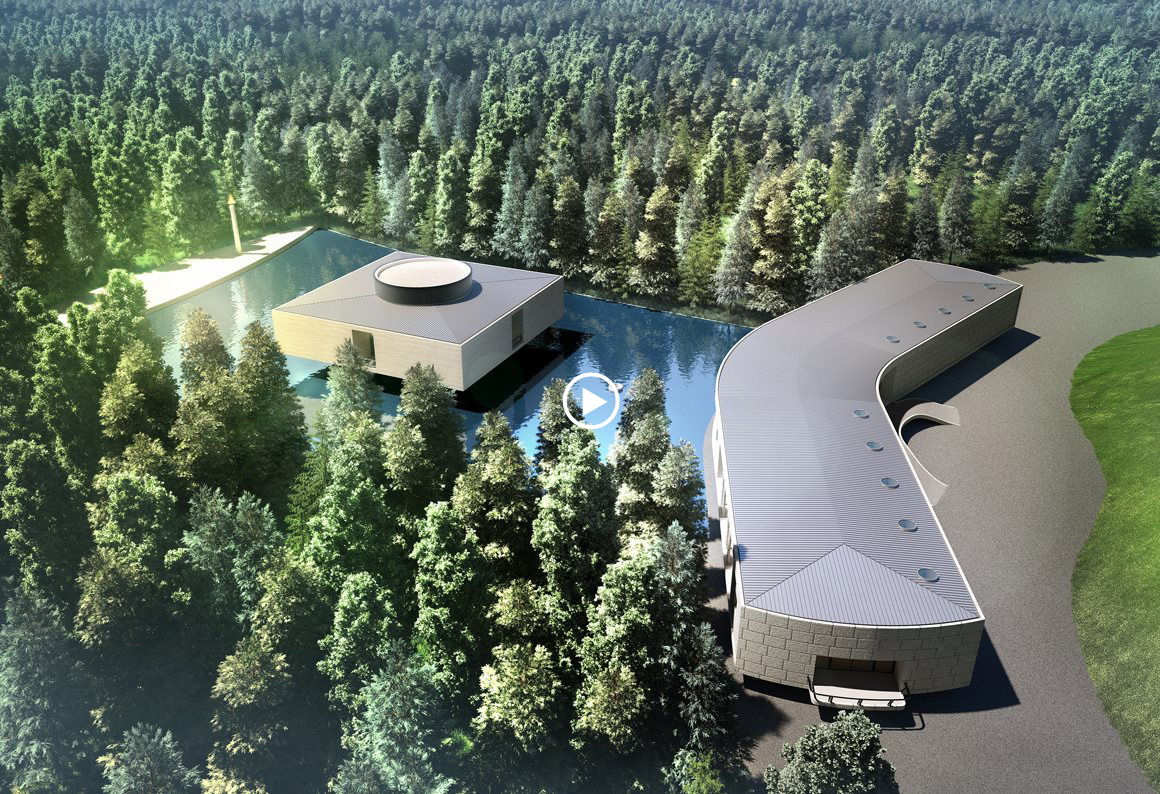

このサイトは白井晟一(1905-1983)によって1955年に計画された「原爆堂」の建設を実現するための活動の一環として開かれた「白井晟一の原爆堂」展(2018年6月)を受けて、展覧会で製作、公開されたCG動画、プロモーションビデオ、年表と、それに加えて展覧会をご覧になった方たちのアンケートを引き続き公開するものです。

また原爆堂計画および建設活動にかかわる情報、議論、企画等をアップしてまいりますのでよろしくお願いいたします。

原爆堂プロジェクト

"野外に出て無限な蒼穹を仰ぐとほっとする。これが理想の色かと思う。生きている本当の理由が、身内に湧いてくるのである。自然の叡智が人間の自由な生命をあらゆる強制から解きほぐしてくれるからだ。"

白井晟一のエセー「めし」の冒頭です。この2年前かれは「原爆堂 TEMPLE ATOMIC CATASTROPHES」のプロジェクトに取り組み、広島、長崎の市民を襲った原爆による残虐、荒涼とした廃墟の世界と向きあっていました。「無限な蒼穹」が燃え上がり粉々に砕け落ちた世界。「自然の叡智」に反して人間が創り出したもの、その爆発とともにアレントの言う「現代」の世界がはじまったのでした。

原爆の威力をさらに高める研究と開発が冷戦下の米英ソでしのぎを削っていたさなか、1954年3月にビキニ環礁で行われたアメリカの核実験で、日本の漁船「第五福竜丸」が被曝し、乗組員23人全員が急性放射能症を発症、無線長は半年後に亡くなりました。核実験によるマグロや海産物の放射能汚染、放射能雨の検証が行われ、3千万を越える署名運動は大気圏内と海洋での核実験禁止にようやく向かわせます。

この状況の中で、映画や文学、漫画や写真、美術や音楽などの様々の分野で原爆や核を問う作品が改めて生まれ始めました。映画では『ゴジラ』(本多猪四郎)、『生きものの記録』(黒澤明)、『第五福竜丸』(新藤兼人)、『二十四時間の情事』(アラン・レネ)などがよく知られています。建築では核の問題と対峙する表現は唯一「原爆堂」計画にとどまり、丸木夫妻の「原爆の図」美術館への提案という形で1955年4月に新聞等に発表され広く知られましたが建設には至らず、白井は8月には機能を美術館に限定しない形で、国際社会に向けた英文パンフレットを作成します。

2011年3月、没後30年を控え「白井晟一 精神と空間」展が「原爆堂」計画を中心に東京で開催されていました。11日、東北地方太平洋岸を大地震と津波が襲い、その中で福島の原子力発電所がレベル7の大事故を発生。核に潜在する脅威が現実のものとなって目の前に突き付けられ、「原爆堂」に託されていたメッセージが60年を経ていっそう切実な意味合いをもって届けられることになってしまいました。展覧会で「原爆堂」計画を見た作家福永信氏のコメントが印象に残ります。「過去のかなわなかった建築ではなく、むしろ未来の建築として映る」

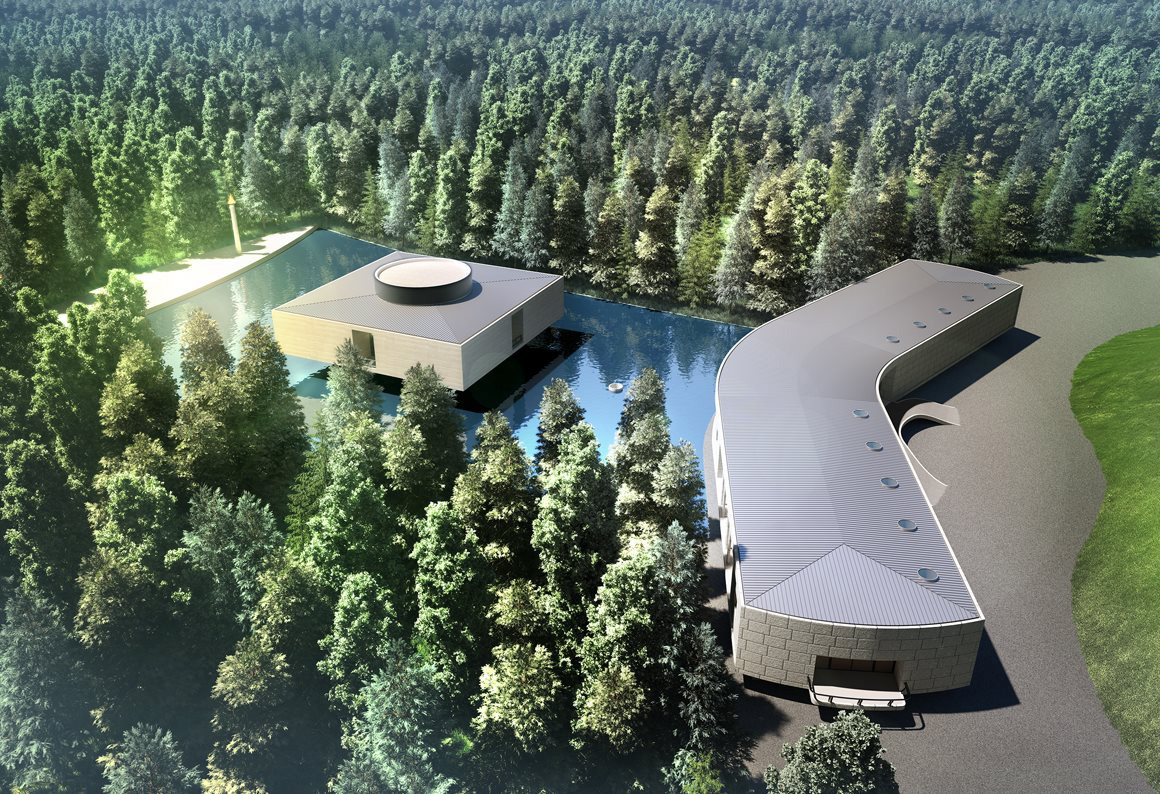

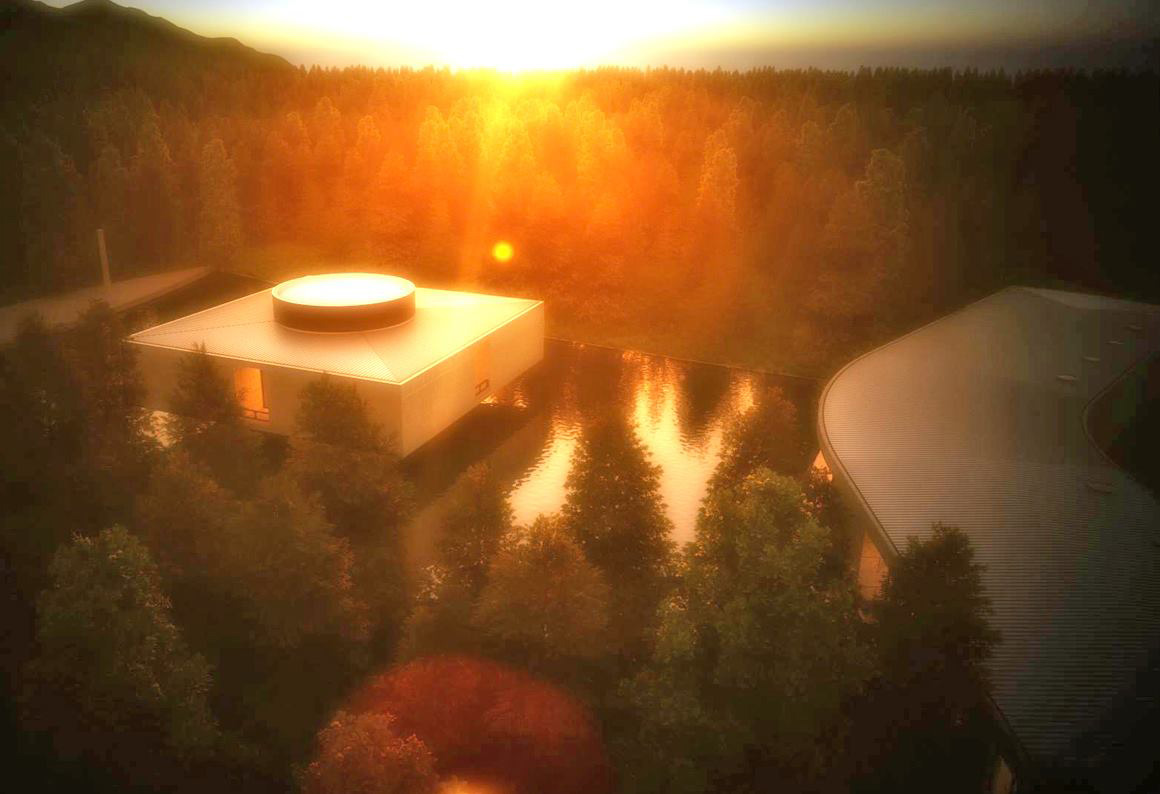

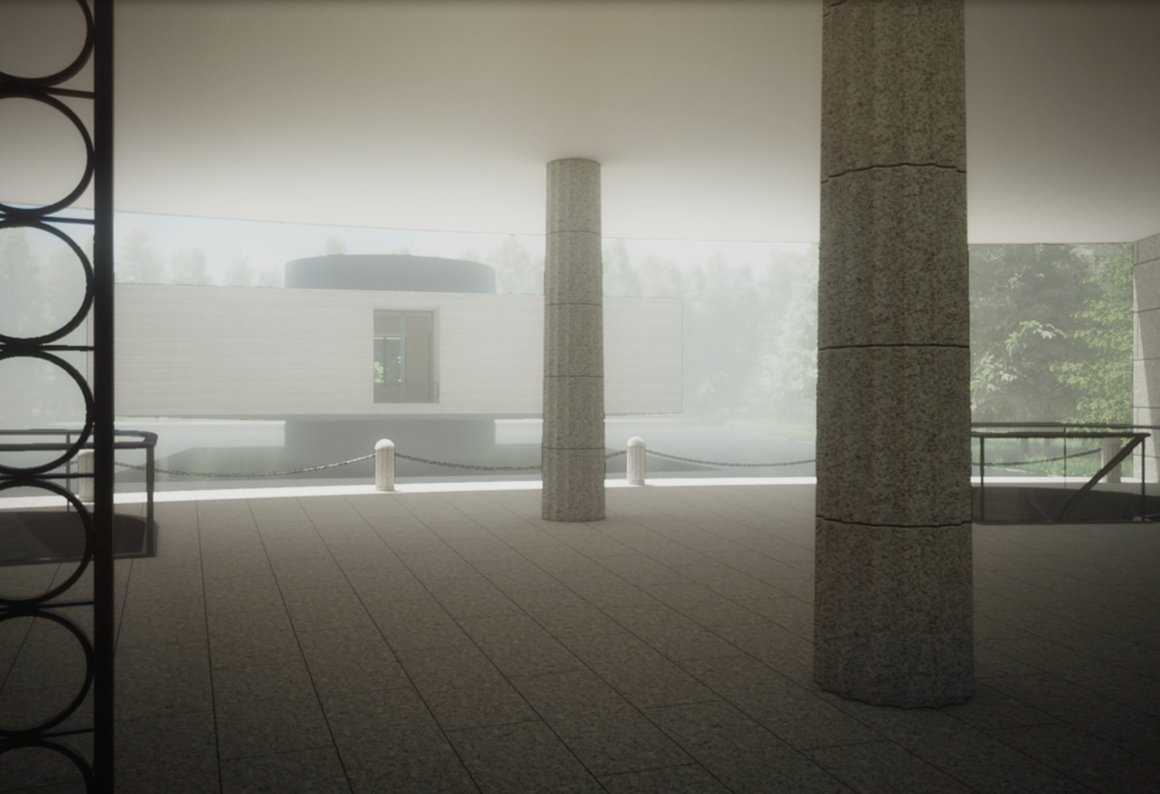

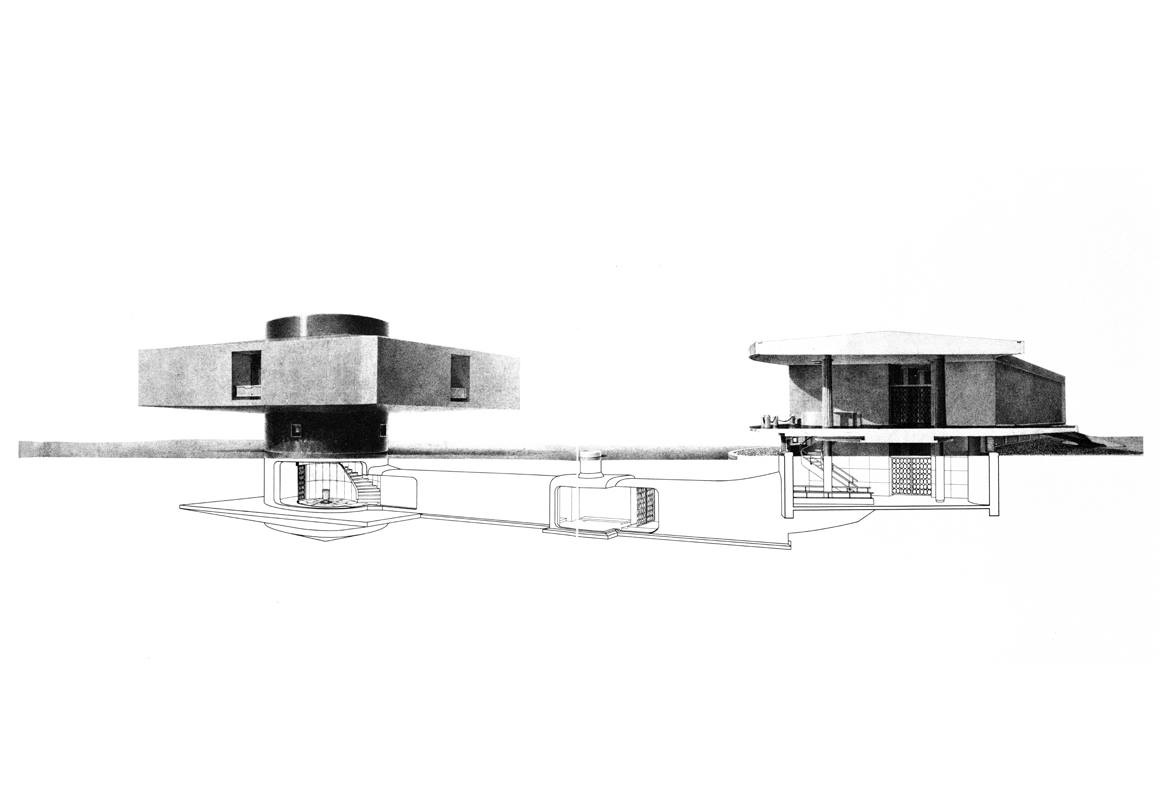

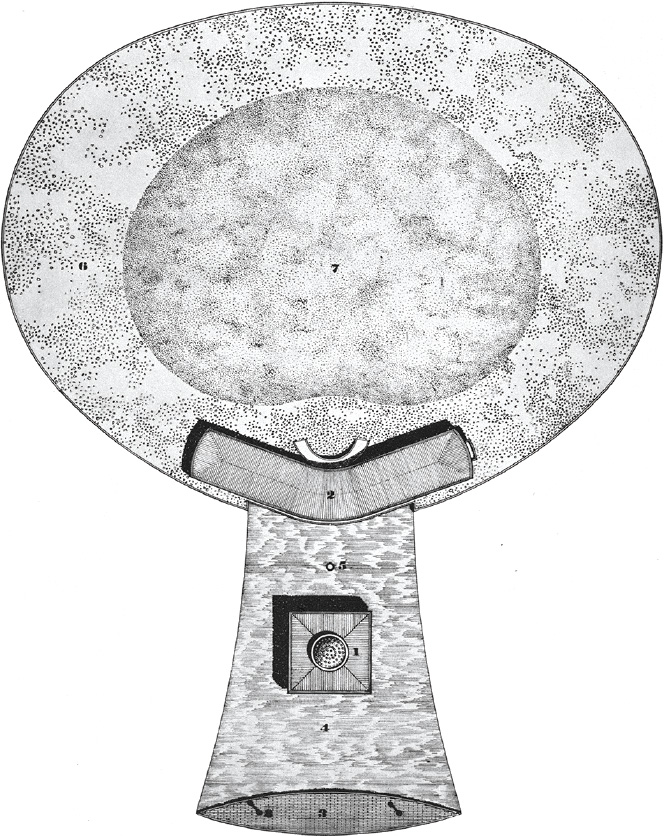

「原爆堂」計画は一枚の精細に描かれたパースと数点の基本図面及び設計者の短いコメントで構成されています。白井の建築家としての活動、エセーを含むさまざまな表現とそれらの背景になった時代に目を向けながら計画の内容と意図を、少しでも全体的かつ正確に把握するための作業を続けています。

唯一の被爆国、核の被害者であったこの国とわれわれは、福島の原発事故を起こしたことによって自国の市民の犠牲ばかりでなく、海洋と大気に放射能を拡散し核の加害者の立場を余儀なくされました。「原爆堂」の建設に向かう活動を促したのはそのことでした。再びヒバクシャを生んではならない、自分たちと同じような凄惨な経験を如何なる人々にもさせてはならない、そうしたヒバクシャを中心とする悲願と活動をとおして育てられた暗黙の了解は、戦後形成された国民的合意の一つであり、日本という国のアイデンティティーを形成してきたものではなかったのだろうか。フクシマはその合意とアイデンティティーを破壊するものでした。

核による脅威を一気に取り払う方法があるのであれば言うことはありませんが、世界を壊滅することのできる脅威から解放される道は遥かに遠いというのが、多くの人の共有する実感でしょう。そのような困難な現実から目をそらすことなく、人間と核の問題を正視し背負い続けることの重要性から、さまざまな形で生まれ隠ぺいされ続けているヒバクシャに対する医療とケアは、国境を越えた国際社会の責務であると考え、「原爆堂」を中心にそのための施設と機構の実現を模索しています。

原爆堂建設委員会

I feel relieved when going outside and looking at the endless blue sky. I wonder if this might be an ideal color. The true reason for living bubbles up inside of my body. Because natural wisdom liberates a free human life from any constraints.

These are the opening sentences of the essay “Meshi” by Seiichi Shirai. Two years prior to this essay, he worked for the “Genbakudo: Temple Atomic Catastrophes” project, addressing the atrocity and the deserted world of ruins, caused by the atomic bomb attacks on citizens in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The “endless blue sky” had shattered to pieces in this world. The “modern” world, as Hannah Arendt referred to it, had begun with the explosion of an object – created by humans in contradiction to “natural wisdom”.

At a time when the U.S., UK, and U.S.S.R. under the Cold War were desperate to promote research and development to further improve the destructive power of atomic bombs, a Japanese fishing boat, the Daigo Fukuryu Maru, was exposed to radiation from a nuclear test by the U.S. at Bikini Atoll in March, 1954. All of the 23 crew members suffered acute radiation syndrome, and the chief radioman died a half year later. This led to examinations of radioactive pollution in tuna and seafood, and of radioactive rain resulting from nuclear tests. More than 30,000,000 signatures were collected, finally moving toward a ban on nuclear tests in the atmosphere and oceans.

In such circumstances, pieces addressing atomic bombs and the nuclear issue began to be created afresh in various areas, such as movies, literature, comics, photos, art, and music. Well-known movies include “Godzilla” by Ishiro Honda, “I Live in Fear” by Akira Kurosawa, “Lucky Dragon No. 5” by Kaneto Shindo, and “Hiroshima mon amour” by Alain Resnais. The only architectural expression confronting the nuclear issue was “Genbakudo” plan, which was published in newspapers in April 1955 as a proposal for the Maruki Gallery for the Hiroshima Panels. “Genbakudo” came to public attention, yet was never constructed. In August, Shirai made a brochure in English for an international society, and he expanded its function to something other than a museum.

In March 2011, the “Seiichi Shirai: Spirit and Space” exhibition was held in Tokyo prior to the 30th anniversary of his death. Its main exhibit was “Genbakudo” plan. On March 11th, the pacific coast of the Tohoku Region was hit by a massive earthquake and tsunami, and the nuclear power plant in Fukushima experienced a major accident with severity level 7. The potential threat of nuclear disaster became real and was thrust upon people. The message in “Genbakudo” was ironically received with deeper meaning after 60 years. Writer Shin Fukunaga saw the “Genbakudo” plan at the exhibition and gave an impressive comment: “It appears to me that it is a future work of architecture, rather than a never-implemented architectural work from the past.”

The “Genbakudo” plan consists of a finely drawn perspective drawing, a few basic drawings, and short comments by the designer. We make continuous efforts to comprehensively and precisely understand the content and intention of the plan as much as possible, while taking into account Shirai’s activities as an architect, various expressions including the essays, and the times as a background.

Japan and its citizens used to be the only victims of nuclear bombing. However, the nuclear accident in Fukushima caused hazards to Japanese citizens, and also unavoidably made the country a nuclear perpetrator, releasing radioactivity into the ocean and atmosphere. This stimulated the efforts to construct “Genbakudo”. No more hibakusha (survivors of the atomic bombings), and no more dreadful experiences for anybody. Such ardent wishes of the hibakusha and others, and a tacit agreement that was grown through their activities constituted a national consensus in postwar Japan. We believe that they had formed an identity of the country of Japan. The agreement and identity were destroyed by the Fukushima accident.

It would be wonderful if we could overcome nuclear threats at once. However, many people share a common understanding that there is a long way to go before we are free of the possible world-destroying threat. It is important to not avert our eyes from this difficult reality, to look straight at the issue of humans and nuclear, and continue to carry the burden. For this reason, we believe that medical services and care for hibakusha – who have been born with various ways and covered up – are a responsibility of the international society beyond countries. With our focus on “Genbakudo”, we seek ways to materialize facilities and a structure for this purpose.

Construction Committee of Genbakudo

白井 晟一Shirai Seiichi

1905年京都生まれ。京都高等工芸学校卒業後、ハイデルベルク及びフンボルト大学でヤスパース等に師事。帰国後は建築家として「秋ノ宮村役場」「浅草善照寺」「ノアビル」「親和銀行」「虚白庵」「松濤美術館」そして「原爆堂計画」などを設計。高村光太郎賞、建築年鑑賞、建築学会賞、毎日芸術賞、芸術院賞、サインデザイン賞を受賞。装丁家・書家としても実績を残し、また、エッセイ集『無窓』(1979 筑摩書房、2011 晶文社)がある。1983年死去。享年78歳。没後1988年に白井晟一全集(同朋舎)が発行されている。2010-11年に展覧会「建築家 白井晟一 精神と空間」(群馬県立近代美術館、パナソニック汐留ミュージアム、京都工芸繊維大学)。

Seichi Shirai, born 1905 in Kyoto, studied German philosophy and the history of architecture at Humboldt University of Berlin and Heidelberg University, was one of the most active and prominent architects of 20th century Japan. His works are characterized by his profound understanding of philosophy. In 1961, He won the Kotaro Takamura Prize, in 1969, Award of the Annual of Architecture in Japan, Prize of Architectural Institute of Japan, Mainichi Art Prize, and in 1980, the Japan Art Academy Prize. His major architectural works are Akinomiya Village Office (1951), Matsuida Town Office (1956), Asakusa Zenshoji Temple (1985), Shinwa Bank Tokyo Branch, Ohato Branch, Sasebo Main Building (1963, 1963, 1969), Kureha-no-le Residence (1965), Kohaku-An Residence (1970), Syoto Art Museum (1980), Sekisui-Kan (1981). He was also known as a calligrapher, having published Kosikyo-shojo in 3 volumes. His essays were published under the title “Muso”(no windows).